In her new painting Monterey (2021), Jamian Juliano-Villani depicts a red wheelbarrow in the snow, inside of which are two baby dinosaurs and a black-and-white POW flag. The dinosaurs are copied from an old Seventies comic, and the POW * MIA (Prisoners of War * Missing in Action) flag was designed in 1972 by the National League of Families of American Prisoners and Missing in Southeast Asia, as a way of keeping alive the memory of all the servicemen still missing or unaccounted for in Vietnam. This setting, she says, is of a US Army veteran’s backyard. She thought of adding a turkey painted in handprints, or a sexy fox burying a T-shirt that says, “It’s a boy,” but settled in the end on this particular combination of dinosaurs, flag and wheelbarrow. It’s an absurd combination, but also feels right and makes sense as an American image: cartoonish, soaked in

In her new painting Monterey (2021), Jamian Juliano-Villani depicts a red wheelbarrow in the snow, inside of which are two baby dinosaurs and a black-and-white POW flag. The dinosaurs are copied from an old Seventies comic, and the POW * MIA (Prisoners of War * Missing in Action) flag was designed in 1972 by the National League of Families of American Prisoners and Missing in Southeast Asia, as a way of keeping alive the memory of all the servicemen still missing or unaccounted for in Vietnam. This setting, she says, is of a US Army veteran’s backyard. She thought of adding a turkey painted in handprints, or a sexy fox burying a T-shirt that says, “It’s a boy,” but settled in the end on this particular combination of dinosaurs, flag and wheelbarrow. It’s an absurd combination, but also feels right and makes sense as an American image: cartoonish, soaked in nostalgia, spiked with darkness. The painting, like the rest of the exhibition, hops and skips back across the country’s history, and the different ways in which the country likes to imagine itself, and was inspired in part, though only in part, by William Carlos Williams’s short, pastoral poem “The Red Wheelbarrow”, from 1923:

“so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens”

There’s a lot of poetry, and free association, in Jamian’s approach to making art. She says she enjoys writing more than painting, and comes up with new ideas all the time, around the clock. She scribbles down lists of ideas and keeps them in boxes in her studio in Bushwick, Brooklyn, labelled by year and stacked up in the corner. When she needs inspiration, she pours one of these boxes out over the floor and the ideas come flowing out:

“OLD CAST IRON SCOTTISH DOG HOLDING OPEN THE DOOR TO AN ENTIRELY NEON ANTIQUE STORE” “METAL RABBI BLESSING RADIATOR” (a favorite of hers) “TWO BUSINESSMEN TOASTING WITH AN AMBER FOSSIL EGG AND A CHAMPAGNE GLASS IN UPSCALE CHINESE RESTAURANT” “TOBOGGAN GOING DOWN THE HILL WITH THE ROSETTA STONE ON IT, A HANDPRINT OF FROG IN PRIMARY COLORS” “A DOG IN THE SNOW WITH A LEMON IN ITS MOUTH”

When I go visit, her dog Timmy, who’s appeared in some of her paintings, runs around the studio with a robotic tarantula in his mouth. He sits down on her pile of ideas and makes himself comfortable.

Her latest robotic sculpture, Armen (2021), which has a room of its own in Stavanger, is made of the plastic red cups Americans traditionally drink from at parties. It dances around on a ping pong table. It’s the college drinking game of beer pong brought to life. Right Said Fred’s 1992 pop smash “I’m Too Sexy” plays on a loop. A bale of hay sits on a rocking chair. This could be a scene from a drunken college party anywhere in the US, from any point over the last three decades.

Playing on the wall is a video from the 1960s of Dutch abstract painter Karel Appel attacking one of his canvases, bashing paint onto it in a thick impasto, like a robot, or a drunken frat boy wanting to wrestle his friends.

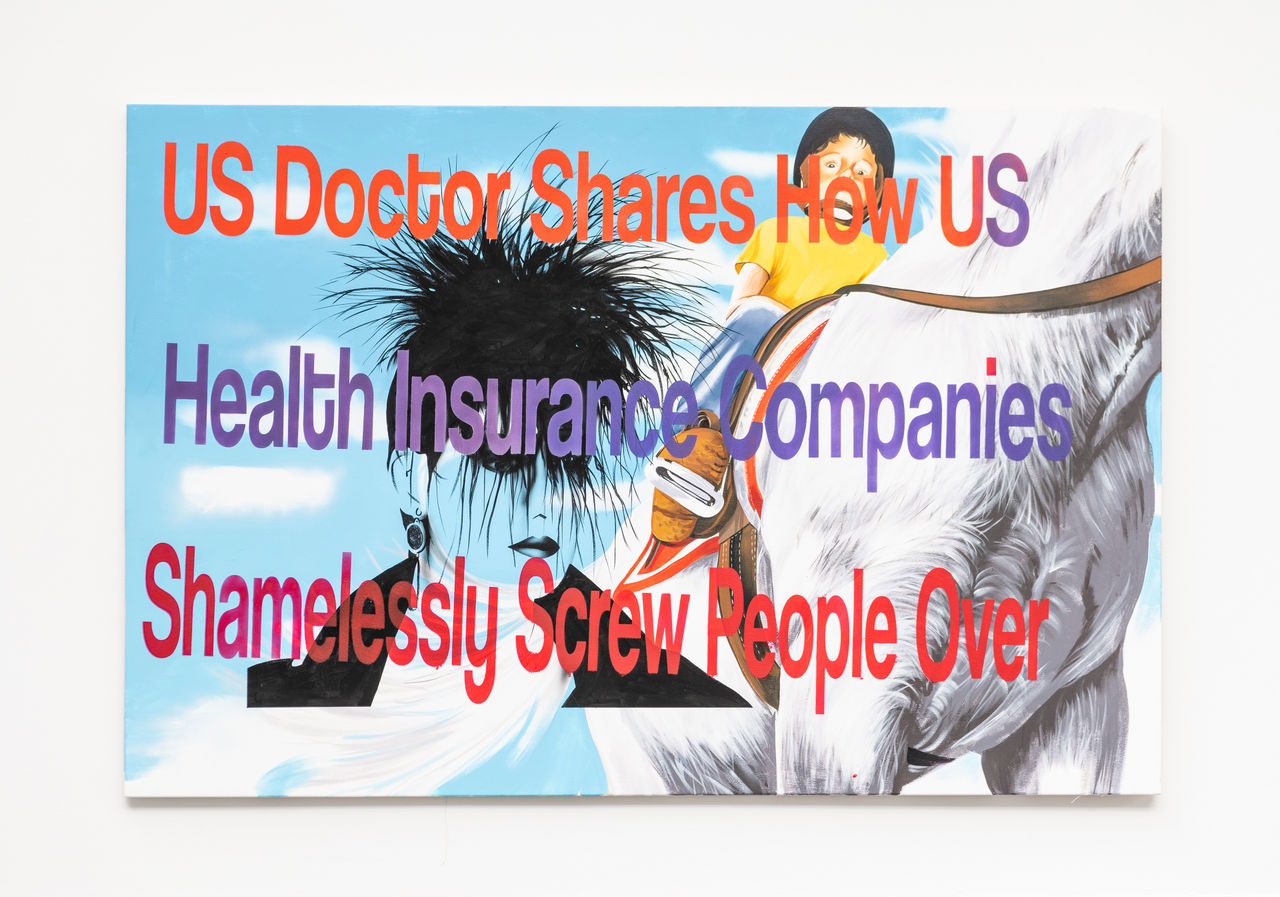

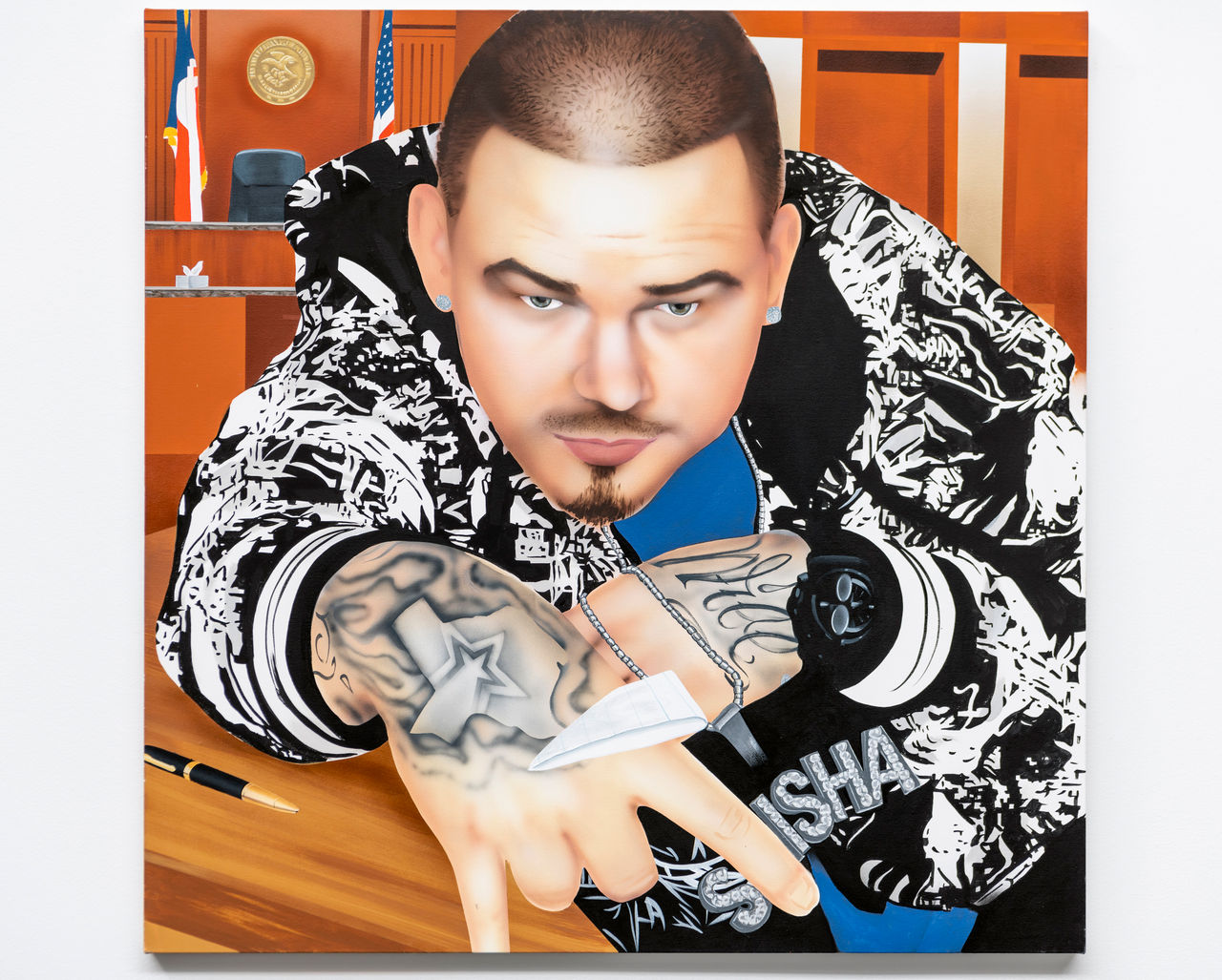

Jamian, however, takes the opposite approach to Appel’s vigorous expressionism. When she’s found an idea she’s excited about, she beams her source material onto her canvases with a digital projector and paints them in carefully with an airbrush, and in places very precisely by hand with a brush, to give a perfect finish. She’s so skilled at this that her compositions don’t look like they’ve been painted freehand. It’s a style that’s inexpressive, commercial, and perfectly flat; that’s more often used on cars and signage than in paintings. Her parents own a commercial printing shop in New Jersey, so Jamian grew up surrounded by finishes like these, and bold fonts and stock images; the style she paints in is also the one she grew up inside. In Robbi Company (2020), which she describes as a sort of self-portrait, she’s painted her family business’s logo and tagline overlaid on an image of the Milky Way.

Many different histories of representation are present in these paintings: old advertisements, graphic art, pop culture, comics, toys, and art too. Bacon Boy (2018) depicts a figure borrowed from a painting by Danish outsider artist Ovartaci, or Louis Marcussen (1894–1985), who was in 1929 committed to the psychiatric hospital in Risskov, where she painted the imaginary beings from her visions. Having first discovered her art in a pile of discarded books she found on the street, Jamian is now a fan and references her often. Her own Bacon Boy is copied straight from an Ovartaci painting, except now he’s made of bacon. In her world, all images and things can have multiple lives; can appear in new forms, in unexpected contexts.

As well as using found images as sources, Jamian often builds out scenarios in the studio and photographs them. She builds sets. For Does This Slide Or Do I Pull (2018), which shows a frog with a big ass slumped on a ladder staring at the wall, she took a toy frog she found in a junk store and photographed it. In real life her plush toy doesn’t have such a fat ass or melancholy air, and he’s holding a heart out in front of him; but because he’s facing the other way in the picture, we can’t see that, we only see him staring at the blank space where his shadow should be.

A different kind of set was made for Take Five (2018), which shows a masked Venetian clown, a Pagliacci-type figure, encircled by his own menacing reflection. She had found an image of a clown she liked, but she was stuck, and didn’t know what to do with it; so she consulted a book of ideas and activities she sometimes turns to in hours of need, Nicolas Rourkes’ Art Synectics: Stimulating Creativity in Art (1984), which inspired her to rephotograph the image surrounded by shiny, reflective mylar. Doing so became a way of warping this weird, slightly unsettling image into an even weirder, more unsettling one; as did the addition of a Louisville Slugger baseball bat, daintily brandished in two white-gloved hands. It’s a hazily sinister image, which reminds her of the films of Kenneth Anger. It’s a touch satanic. A scene from a masked ball you wish to attend but are afraid of. There are hints of violence throughout her paintings, but it’s a slapstick, unthreatening cartoon violence. Darkness seeps in around the edges of kitsch.

In her candy-floss pink bathroom painting Replace Phosphates Without Compromising Functionality, a Relief (2020), the trash monster from David Lynch’s film Mulholland Drive (2001) comes crawling out of the toilet and looks right out of the canvas. She represents, in the painting as in the movie, dark, frightening emotions we keep hidden deep down inside of us, the garbage within our souls; or perhaps she’s the fear of failure, the dark side of the American Dream, hidden inside your toilet, around the U-bend, waiting for you. Placed in front of the painting is a stepladder, much like the one the thick frog sits on, inviting viewers to climb up into the toilet and embrace their worst fears, and throw themselves in.

When she makes an artwork, Jamian often likes to start with the stupidest idea she can think of, and then pare it back, or make it even more stupid, until she finds her balance, the sweet spot. A bad joke, or a visual gag or some toilet humor, helps put everyone at ease. Shut Up, the Painting (2018) shows a stop-light that reads “SHUT UP.” It’s so dumb, she’s said, that it cancels itself out, and can’t really be talked about. The idea of the painting is stupid. The idea is that there is no idea.

The traffic lights tell you to shut up, but Jamian never really shuts up. She talks and talks, flitting quickly across topics, and writes down and collects ideas and puts them in boxes, and tips them out on the floor of the studio, like a trash heap, one that’s dotted with riddles and bad jokes and gold nuggets. The frog with the butt. Pagliacci with the baseball bat. These are dissonant images: scribbled-down one-liners made into visual nonsense poetry. America, like the rest of the world, is a land of contrasts and absurdities, and she revels in this. She wants, I believe, to both experience and somehow express the complete absurdity of reality.

Her art is confusing. People like things that are confusing, because they like to be confused. However, Jamian trades in a different sort of confusion to most of today’s confusing art. Her approach is not high-conceptual or obscure, but rather playful and relatable. She takes popular everyday images and objects and twists them into something uncanny. Just as her print shop painting is a self-portrait, her clowns and trash monsters and bacon boys might also be read as avatars of her. She has a genuine love of trash images, and a disregard for ideas of good or bad taste. Her personal taste, she has said, has nothing to do with it. She tries not to care about how her paintings look; because once she stops caring, and lets go, is when things become exciting. It’s good not to worry too much about making mistakes.

What matters for her are ideas. That’s what’s most important: the ideas behind her paintings, and the effect they have on you. If they give you a feeling of déjà vu, that’s good. If you can’t make up your mind what to think about them, that’s good. These are paintings of a place that seems familiar, but also off, also quite wrong.

- Text by Dean Kissick

The exhibition was produced in collaboration with JTT Gallery and Massimo De Carlo.

b. 1987

Jamian Juliano-Villani (b. 1987 Newark, NJ) lives and works in Brooklyn. Recent solo exhibitions include Mrs. Evan Williams at JTT in New York, Let’s Kill Nicole, at Massimo De Carlo in London, Sincerely, Tony at Massimo De Carlo, Milan, The World’s Greatest Planet on Earth at Studio Voltaire, London, Nudge the Judge at Tanya Leighton in Berlin, and Detroit Affinities at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Detroit. Her work has recently been included in group shows at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Jewish Museum, MoMA PS1 and the Brooklyn Museum, the Hammer, Los Angeles, Kunsthal Rotterdam and the MAXXI Museum in Rome.

Dean Kissick is a writer and New York Editor of Spike Art Magazine. His column “The Downward Spiral” is published on Spike on the second Wednesday of every month. He’s recently written texts for Matt Copson’s show at High Art, Paris, Amalia Ulman’s film companion for El Planeta, published by Arcadia Missa, London, and Pieter Slagboom’s forthcoming monograph.