There’s a scene in the Spanish psychological thriller The Skin I Live In, directed by Pedro Almodóvar that comes to mind when I think of Jonathan Baldock’s anthropomorphic sculptures. In it, we see the central protagonist, plastic surgeon Dr. Robert Ledgard develop a synthetic skin that could save the lives of burns victims. Filmed from a bird’s-eye perspective overlooking a surgeon’s operating table; fragments of skin are pieced together across a terrain of blue surgical markers etched onto a mannequin that then morphs into the neck of his subject (or victim) Vera Cruz. Here, the fabrication of skin is a form of art and plastic surgery is equivalent to artistic expression [1]. Baldock’s art conjures various references, or nods to, art history, literature, and popular culture. Albeit not explicitly, the use of iconography is used in a way to invite the viewers to delve into their own connections — acutely

There’s a scene in the Spanish psychological thriller The Skin I Live In, directed by Pedro Almodóvar that comes to mind when I think of Jonathan Baldock’s anthropomorphic sculptures. In it, we see the central protagonist, plastic surgeon Dr. Robert Ledgard develop a synthetic skin that could save the lives of burns victims. Filmed from a bird’s-eye perspective overlooking a surgeon’s operating table; fragments of skin are pieced together across a terrain of blue surgical markers etched onto a mannequin that then morphs into the neck of his subject (or victim) Vera Cruz. Here, the fabrication of skin is a form of art and plastic surgery is equivalent to artistic expression [1]. Baldock’s art conjures various references, or nods to, art history, literature, and popular culture. Albeit not explicitly, the use of iconography is used in a way to invite the viewers to delve into their own connections — acutely exposing how the language of art can unite us.

For his first exhibition in Norway, Baldock presents a new body of work, many of which were made during lockdown in London at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. Concerned with the meditative nature of making, Baldock’s multidisciplinary practice encompasses sculpture, painting, textiles, ceramics and performance whereby hand-made and domestic techniques are central to its production, explaining that “ideas associated with craft have been dismissed as sentimental and nostalgic” and he “believes in the power of making things, and the bringing together of head and hand.” [2] Often biographical, Baldock weaves together themes of mythicism, folklore, spirituality and sensuality to explore the fleshy, malleable quality of the human form and our inner psyche.

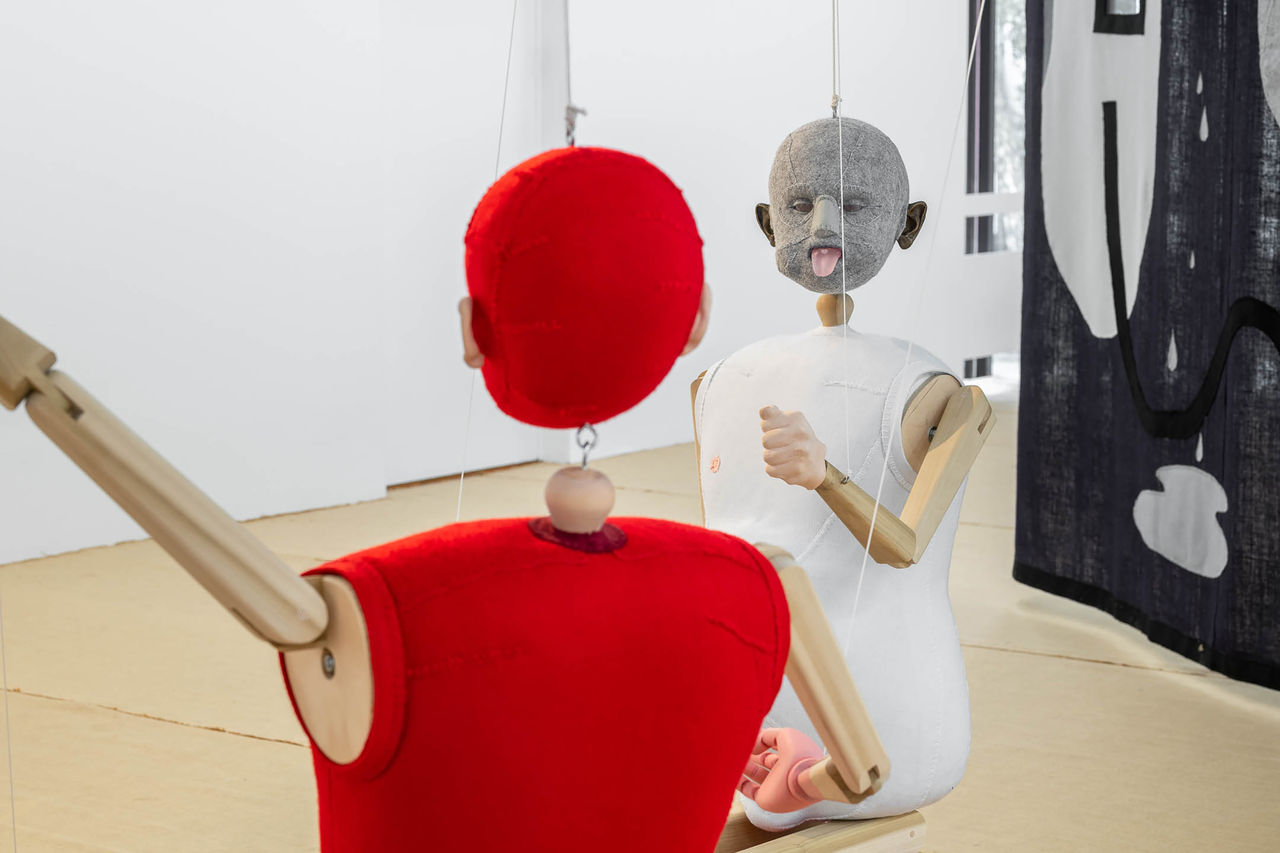

Drawing on the illusion of theatre and puppetry, Baldock presents the viewer with a mise-en-scène comprising life-size marionettes that act as avatars or extensions of the artist, fabric hangings, and ceramics that play with the performative potential of material, objects and sculpture. Like the themes inherent to The Skin I Live In, the works in this exhibition are rooted in the idea of the social skin [3] and grapple with the disconnect between how one presents themselves outwardly and what they are inside — addressing the trauma, anxieties, mortality and spirituality around our relationship to identity, the body and the space it inhabits.

Upon entry, the visitor is greeted, or confronted by, a marionette that seems to assume the role of a theatre usher. Constructed through felt, wood, string, and bronze and ceramic casts, further figures populate the gallery space: laying limp on a four-poster bed or propped up on the floor with their limbs contorted to resemble a table as if left out on the stage after a production. The marionettes seem to rebel and resist their innate abilities of what it means to be a puppet, proposing potential for agency from the viewer’s imagination — breathing life into the inanimate.

Their bodily proportions are stretched, compressed and exaggerated. Stitch work resembling surgical incisions that puncture the skin hold together pink, red and grey felt that stretches over the marionette’s wooden skeletal torsos and heads. Holding traces and imprints of Baldock’s body (casts of disembodied ears, hands and feet that bear the pores and creases of skin) render the figures with a humanistic quality whilst blurring the binaries of gender — some of them have swelling stomachs signifying pregnancy, a ravaging cyst or even the effects of indulging in too much beer.

Fantastically camp and equally sinister and grotesque; protruding mouths suggest blowing bubble-gum, whistling and puckering for a kiss whilst others poke out their glass tongues or in one case, expose a finger. Here, the cast of characters mimic the most natural and mundane human actions and expressions in such a way that they become strange in the spectator’s eye. [4]

Adding to the theatricality of the gallery as a stage, textile hangings ascend from the ceiling and act as metaphorical walls or curtains to separate the external and internal worlds — performer and audience. Physically large, thus confronting the visitor and instructing them to shuffle in and around the space, the first fabric hanging the viewer encounters, Puppet Master, depicts two hands attempting to manipulate and animate a puppet’s actions as the disconnected strings tangle between the fingers and sag on the floor beneath them. As the puppeteers role is to not appear on stage, Puppet Master somewhat resembles the collapse of illusion, serving as a metaphor for the loss of power and control.

Elsewhere, the artist pays homage to human’s relationship with animals. In the largest of the hangings titled The Horse is a Mirror to Your Soul, a horse is seen gazing into a mirror whilst appearing to be pregnant with a human. Horses have been the subject of artistic production since as early as cave paintings to Eadweard Muybridge’s 1873 stop motion film The Horse in Motion which aimed to determine whether a galloping horse is ever fully airborne. The majestic presence and physical strength of horses, have been a concern for Baldock, particularly the ways in which humans have coexisted and domesticated them — through means of transportation, agricultural and warfare. This work highlights humanity’s domination over the natural world whilst simultaneously looking at how, symbolically, horses have featured as an emblem of freedom and strength. Upon closer inspection the horse is seen excessively salivating and forming a pool of white substance on the floor. Again, indicators of collapse are conjured within the work, as this can be a sign of viral arteritis, fever and depression. [5]

Baldock’s interest in theatre is further explored in a series of casts of the artist’s face. Here, the pastel-toned masks portray Baldock grimacing or frowning in overtly exaggerated expressions and can be seen as a direct reference to the imagery of the ‘Sock and Buskin’ [6] that serve as the representation of joy and sorrow, two emotions integral to the narrative arc of a theatrical play. Masks, a longstanding motif in Baldock’s practice act to conceal, disguise, and perform, whilst now they take on a new role of the protector to prevent infection.

Baldock’s immersive exhibition encourages the viewer to enter a psychological world that revels in the performative properties of sculpture and is imbued with a magical, ritualistic power. It seduces and repels in equal measure. As artist and maker, subject and object, Baldock positions his own body at the heart and interception of his sculptural practice, aptly serving the words of Beyoncé, which lends itself to the title of the exhibition, “Me, Myself and I, that’s all I got in the end.” [7]

Text by Chris Bayley

Footnotes

1. Tarja Laine, Art as a Guaranty of Sanity: The Skin I Live In. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media 7, Summer 2014, alphavillejournal.com/..., accessed: 6 September 2020.

2. Molly Taylor, Interview with Jonathan Baldock, frameweb.com/article/..., 8 October 2018, accessed: 5 September 2020.

3. The ‘Social Skin’ or the ‘Social Body’ is a socio-theoretical concept that looks at the surface of the body (hair, fashion, cosmetics etc) and its relationship with the social self and the psycho-biological individual. See Terence S. Turner, ‘The social skin’, journals.uchicago.edu/....: 7 September 2020.

4. Jena Osman ‘The Puppet Theater Is the Epic Theater’ in Ingrid Schaffner and Carin Kuoni, eds, The Puppet Show (Philadelphia: Institute of Contemporary Art, 2008), p.19.

5. Stacey Oke, Hypersalivation in Horses, thehorse.com/149850/..., accessed 5 September 2020.

6. The Sock and Buskin are often referred to ancient Greek symbols of comedy and tragedy, and are widely represented in the form of two masks. In Greek theatre, actors portraying the role of the tragedy wore a boot (buskin) whilst actors portraying comedy would wear one loosely fitted shoe (sock).

7. Beyoncé Knowles, “Me, Myself and I”, Dangerously in Love, Columbia Records, 2003.

The exhibition has received generous support from Stephen Friedman Gallery, London.

b. 1980

Jonathan Baldock (Kent, UK) works across multiple platforms including sculpture, installation and performance. He graduated from Winchester School of Art with a BA in Painting (2000-2003), followed by the Royal College of Art, London with an MA in Painting (2003-2005). Baldock’s work is saturated with humour and wit, as well as an uncanny, macabre quality that channels his longstanding interest in myth, folklore and the narratives associated with 'outsider' practices. With work often taking on a biographical form, Baldock addresses the trauma, stress, sensuality, mortality and spirituality around our relationship to the body and the space it inhabits.

In the Spring of 2019, Baldock had a solo exhibition at Camden Arts Centre, London, which toured to Tramway, Glasgow in August 2019 and Bluecoat, Liverpool in March 2020. Other notable solo and two-person exhibitions include those at De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill (2017); The Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool (2017); Southwark Park Galleries, London (2017); PEER, London (2016); Chapter Gallery, Cardiff (2016); Wysing Arts Centre, Cambridge (2013). Baldock is represented by Stephen Friedman Gallery, London.

Chris Bayley is a curator and writer based in London, where he has been Curatorial Assistant at Barbican Art Gallery since 2017, working on Masculinities: Liberation through Photography (2020); Modern Couples (2018) and Yto Barrada: Agadir (2018). He is also Associate Curator at VITRINE, London and Basel.